The History of Royalties for Visual Artists: and why are they important?

The History of Artist Royalties

FairArt was founded on the principle that buyers, sellers, and artists themselves should be made to feel equally welcome, with transparent pricing and an innovative royalties model that, for the first time, would enable artists to be properly compensated for secondary sales of their work.

It sounds like an intuitive idea, yet there is actually no international law in place that makes it mandatory for artists to benefit from the resale of their work.

Where did artist royalties come from?

The primary ‘law’ in place that offers some sort of protection for artists is known as the Artist’s Resale Right (ARR). Originally known as the droit de suite, the right was first proposed in France following the sale of French realist painter Jean Francois Millet’s 1858 painting, L’Angélus, in 1889. The owner of the painting, the copper merchant Eugène Secrétan, made a huge profit from this sale. He sold it for 553,000 francs after buying it from the artist for 1,000 — whereas the artist and his family were struggling to get by.

Jean-François Millet, The Angelus (1858)

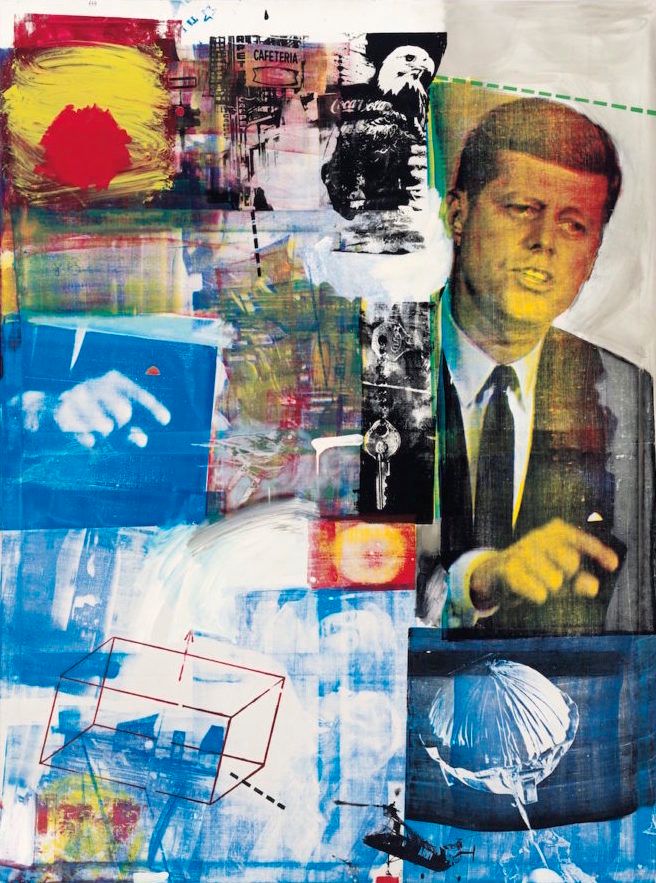

Jean-François Millet, The Angelus (1858)Fast forward: the debate over artists’ royalties was set alight in the US in 1973 when Robert Scull, the owner of a New York City taxi fleet, sold off the bulk of his noted Pop Art collection at Sotheby’s. In the process, he earned $85,000 for a painting by Robert Rauschenberg that he had bought 15 years earlier for $900. After the sale, Rauschenberg came up to the collector and said, 'I’ve been working my ass off for you to make that profit?'

Rauschenberg’s sense of injustice is still being felt by artists around the world. The art world has come a long way in democratising creativity, but has yet to democratise ownership. There is still no existing international framework for artist compensation. The Berne Convention of 1971 enshrines authors and artists with an ‘inalienable right to an interest’ in the resale of their work, but has no legal force in the absence of national legislation in implementing it.

Where in the world do artists get paid when their work resells?

France was the first country to implement the droit de suite in 1920. The 2001/84/EC directive mandated a somewhat uniform system across the EU, while the ARR was only introduced into UK law in 2006 — and only applied to living artists. It was only in 2012 when the right was extended to include the estates of deceased artists. The right lasts for a copyright period of the life of the creator and 70 years after the creator’s death. The U.S. doesn’t have a national artist royalty scheme, along with Canada, China, Japan, and Switzerland.

In the United States, only the state of California has implemented a law, called the 1977 California Resale Royalties Act (CRRA), that requires fine artists to be paid royalties when their artwork is resold. Artists were entitled to five percent of the resale price of their artwork. However, there were restrictions to the law: it only applied to works sold in California, or sold by a resident of California.

However in 2018, the Ninth Circuit of the US Appeals Court struck down the law, claiming that only works resold when the CopyRight Act became effective (1 January 1977 to 1 January 1978) would be eligible for royalty payment. Why is there push back against artists getting paid?

Robert Rauschenberg, Buffalo II (1964)

Robert Rauschenberg, Buffalo II (1964)The current system seems to benefit everyone except for the artists. It is therefore perhaps unsurprising that the biggest players in the market, the ‘mega dealers’ who have the power to enact real change, have remained silent for so long. Despite being the industry’s lifeforce, artists are treated as outsiders. In an occupation that lacks benefits, workers compensation, and pensions, there is a desperate need for new sources of revenue.

The lack of support for artists has a trickle down effect not just on creative output, but also on galleries. Galleries more often than not have no more than a small number of highly successful artists, and they heavily rely on the profits they make from these sales to invest in the careers of young emerging artists. With high rents and the costly art fair treadmill straining gallery finances, new sources of support for their artists could prove vital in easing the burden of supporting new talent.

Traditionally, the art market has operated on the premise that artists receive payment for their work only at the initial sale, with resale royalties not being a customary part of the system. This entrenched model has been the norm for a long time, leading some stakeholders, including collectors and galleries, to resist changes to these established practices.

There are concerns that introducing resale royalties might disrupt the traditional dynamics of the art market. Critics argue that it could potentially deter prospective buyers and reduce market liquidity by imposing an additional financial burden on sellers. The fear is that such a change could hinder the fluidity of transactions and impact the overall vibrancy of the art market.

Photographer: Don Emmert, Courtesy of AFP/Getty Images

Photographer: Don Emmert, Courtesy of AFP/Getty ImagesWhile the division between primary and secondary sales is found in most industries, the art trade is unique in the extent to which the secondary market dominates value. The sheer size and private nature of the secondary market makes it inherently challenging to quantify, but a comparison between the average sales turnover from primary and secondary market businesses exposes the gulf between the two. It also exposes deep rooted structural injustice in excluding artists from the most profitable segment of a market that would not exist without them. Why is it that artists are expected to work for the long-term profit of others and not themselves?

Unsurprisingly, there is little debate amongst artists. One of the most in-demand artists of today and considered by many the leading light of a new generation of creatives, Nina Chanel Abney, sees it plainly: “If my work resells for a ton of money, it would be great to have some of it . . . all artists talk about it. No one is happy with how it goes. At the end of the day, it’s just all about supporting the artists. I don’t understand who wouldn’t want to participate in that.”

FairArt and Global Royalty Payments

FairArt is building an ecosystem for buyers, sellers, galleries, and charities centred on the artist. By attaching an artist royalty to each transaction, FairArt enables artists to directly benefit from value they have historically created for others. In focusing on the secondary market, FairArt is giving artists a long overdue voice in the most profitable segment of the industry and rebalancing the scales. For too long governments and the establishment have overlooked the welfare of artists. The pandemic helped shine a light on social causes, and it is now the responsibility of new innovative platforms to take the initiative.